Presumably this payment plan has been around since people first started figuring out ways to avoid financial indentured servitude. It is certainly not unique to this site, but is known as one of many possible payment plans. It has some very nice properties for you, and a few of which to be aware.

At the beginning of the loan we owe the most, thus the interest payment we owe is the highest, so the amount of the monthly payment that goes to principal is the lowest. Indeed, in Month 1, next month's principal payment (Month 2) on a 30 year at 6% on $200,000 is just $200.10.

So we are budgeted for $1,688 (the 15 year amount), but let's consider that we pay only the minimum due plus next month's principal: $1,199 + $200 = $1,399. We're under budget!

Now Month 2 arrives. But we've already paid that month's principal. You can just cross a line through that month—interest and all. We would have owed $999 in interest for that month, but because we paid that month's principal just one month early, that $999 in interest is completely wiped out. Zero. We spent $200 one month early and saved $999. That's a good deal.

It is important to note that the $999 savings is only realized, non-inflation adjusted, over the full scheduled term of the loan (30 years). If we pay off the loan early and exit the game we won't see the entire savings. We may think that if we pay $200 thirty days early, then we save only 1/2% of $200 or $1. That is the case if we repay the entire loan at the end of that month and then call the whole thing "quits." But for each month we do not pay back the entire loan, the savings accrue. By paying the $200 thirty days early, the entire loan payment schedule shifts forward one month—so now we will be paid off in 359 months instead of 360 months, etc., etc. That is why in Tip Number Two we think in terms of our total savings, over an entire life's payment span of 15 to 30 years, regardless of the number of mortgages.

So what do we pay in Month 2? It's easy. We'll pay our regular payment plus the next month's scheduled principal (Period 4). The table is below:

Again, we are going to get another month "interest free" simply by paying just the principal just one month early. In Month 2 we pay $1,199.10 + $202.10 and "save" $997. So in two months we paid an extra $200 + 202 = $402 of money we owe anyway, and saved $1,996. That's a great deal.

The benefit of this is greatest at the beginning of the loan, since that is when the differential between the interest portion of the payment and the principal is the greatest—i.e., we get the greatest interest savings for the lowest extra payment. We can stop or restart any time.

If every month we pay two months' principal instead of the usual one month, then the loan will be paid in half the time. This must be so, since we are paying two-for-one. So we will pay off this house in 15 years. This is important for us, because we are committed to a 15 year period, and we see we are paying the loan over 15 years. We took the 30 year loan to set up a buffer for us (a lower minimum monthly payment) in case of bad times.

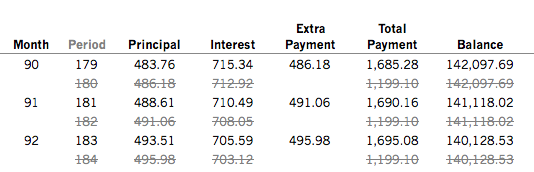

The flip-side of this plan being so attractive by using low extra payments at the beginning of the loan, is that the payments get larger and larger as the loan progresses. That's because "next month's" principal component gets larger. That means that our monthly mortgage payment increases each month—something that can be hard to budget. For example, on month 90 we hit our 15-year monthly budget of $1688:

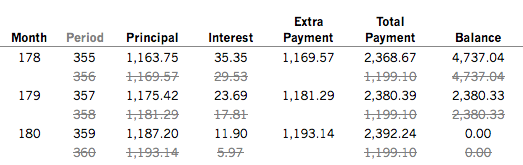

And indeed, by end of the loan, two months' principal is essentially twice the minimum payment. By month 180 the loan is paid off, but the monthly payment has essentially doubled:

So what happened to our monthly budget and wiggle room?

The wiggle room is still there because the loan with the bank was at a fixed rate for 30 years, so the minimum payment in an emergency is still $1,199; well below our budget. This is important for Tip Number One.

But what out our budget of $1,688? We are high by $704, 15 years down the road.

The fix is quite simple.